Could cattails help to solve phosphorus and chloride pollution in some of our lakes and wetlands? A new pilot initiative led by the South Washington Watershed District (SWWD) aims to find out.

Cattails are a familiar sight along the shores of most Minnesota lakes and wetlands. They have long, thin sword-shaped leaves and their seed heads look a lot like corndogs. You can actually eat the young shoots when they come up in the early spring (they taste like cucumber) and the flower spikes can be roasted and eaten like corn on the cob while they are still green.

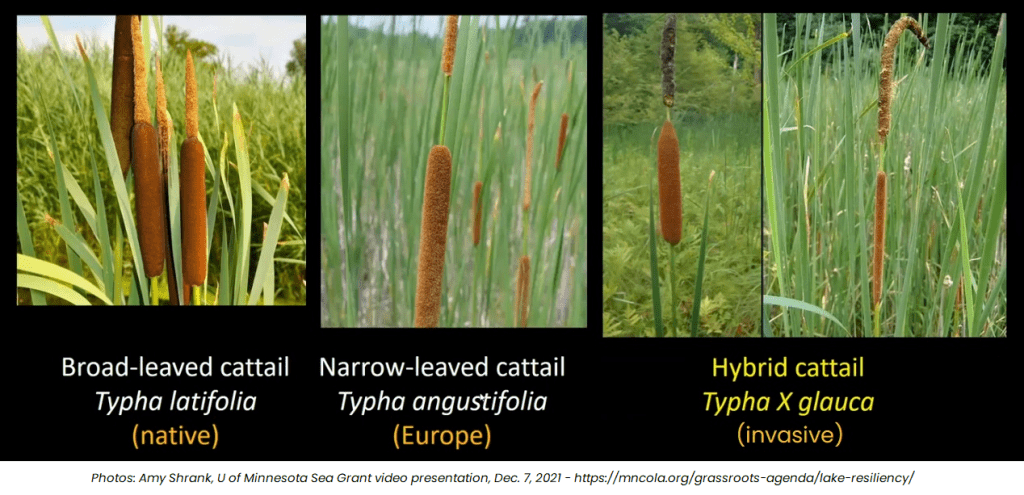

The native broadleaf cattail is found throughout the state and is a beneficial plant that helps to protect lakes from wave erosion and provide habitat for birds and wildlife. Unfortunately, in the Twin Cities metro and southern Minnesota, 82% of wetlands have been taken over by invasive species such as reed canary grass, purple loosestrife, and a nonnative narrowleaf cattail. In addition, narrowleaf and broadleaf cattails can reproduce to form a hybrid, which is also problematic.

Unlike our native cattail, narrowleaf cattails are able to survive in brackish water (a mix of freshwater and saltwater), giving them a competitive advantage along roadways where road salt has increased chloride levels. “That’s actually why they are here in the first place,” explains Tony Randazzo, a Watershed Restoration Specialist with SWWD. “They first showed up in Minnesota in roadside ditches and have basically followed the roadways to move deeper into the state and expand throughout the metro area.”

As cattails grow, they take up available nutrients in the water and soil like a sponge. In particular, they are very good at up-taking phosphorus, and can store anywhere from 10-25% of total phosphorus in the above-water portion of the plant. During the fall, when the plants die back, they return most of the nutrients back to the water and sediment at the bottom of the lake. What would happen, then, if the cattails could be harvested at the end of the summer, before that die-back happens?

In August, SWWD worked with City of Oakdale to clear a 0.5-acre test plot in a wetland connected to Armstrong Lake (south of Hwy 10). Crews hand-cut all of the invasive cattails above the waterline and then sent some of the biomass to a lab for testing. The initial results were impressive.

“The cattails contained a huge amount of phosphorus,” says Kyle Axtell, SWWD Watershed Project Manager. “But we were even more excited about the chloride – 3% of the plants’ total biomass was actually comprised of chloride.”

Extrapolating these results, Randazzo and Axtell estimate that the watershed district could sequester 724 pounds of phosphorus and 5.5 tons of chloride if it were to harvest all of the cattails in Armstrong Lake and its connected wetlands. For perspective, one pound of phosphorus can translate into 500 pounds of algae, and 1 tsp of salt is enough to contaminate five gallons of water.

As promising as these results may be, there are still quite a few logistical challenges that would need to be worked out before cattail harvesting could be scaled-up as a viable watershed management strategy. “The biggest challenge is finding somewhere to dispose of an enormous quantity of biomass, especially if it contains high levels of chloride,” says John Loomis, SWWD Administrator. Landfilling isn’t ideal, but the watershed district also worries about contaminating community compost sites. Before expanding the initiative, SWWD would also need to develop cost-effective strategies for harvesting the cattails in a larger area. Even so, watershed district staff agree that it’s exciting to think about the possibilities.

To learn more about the South Washington Watershed District and projects, including the cattail harvest at Armstrong Lake, visit www.swwdmn.org.